So you’re an American kid taken to the most perfect fairyland in the world. And you don’t like it.

Now what?

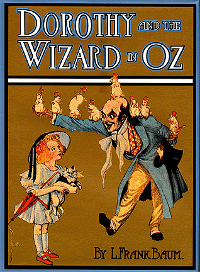

This is one of the major questions posed by Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz, the darkest and most troubling of Baum’s Oz books. The book starts with an earthquake, sending Dorothy, her semi-cousin Zeb, his horse Jim, and her kitten Eureka on an unsettling and unpleasant trip through the center of the earth. There, they meet the Wizard and his Nine Tiny Piglets, some coolly unemotional vegetable people who plan to kill them, some considerably pleasanter invisible people and less pleasant invisible bears, wooden Gargoyles, dragons, and a dead end. Suddenly, Dorothy remembers that Ozma could have saved them at any time, and with a secret hand signal, has Ozma bring the group to Oz. The Wizard is warmly welcomed back and given a home, and Ozma throws a few parties.

But for everyone else, things are less happy. Ozma holds a rather nasty (if hilarious) trial for the kitten, accused of eating a piglet, and sentences the mostly innocent kitten to death. (The kitten did have every intention of eating the piglet, but the piglet got away.) And Zeb and Jim realize that they do not belong in Oz.

In contrast to the tight focused plotting of the previous three books, Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz jumps from disconnected point to disconnected point, tenuously linked in the first half by dark tunnels and stairs and a need to find food, and in the second half, only by the newcomers to Oz finding themselves in an oddly hostile and uncertain environment—odd, since this is supposed to be a delightful fairyland. Baum punctures his ostensibly children’s book with several unpleasant moments. At one point, the Wizard of Oz actually slices someone in half, and later sets fire to the Wooden Kingdom of the Gargoyles, stating carelessly that if the entire country burns down, “the loss will be very small and the Gargoyles will never be missed.” Hi, genocide, and welcome to Oz! (To an adult reader, the Gargoyles appear to be guilty of nothing more than self defense.)

The tone may spring from Baum’s growing fatigue with Oz. (In his prologue he expresses the hopeful thought that maybe, just maybe, children will read his other books.) That fatigue perhaps also explains why none of the characters introduced in this book return for anything more than cameo appearances. Indeed, Zeb and Jim the cabhorse never return to Oz, much less make their homes in the Emerald City, Baum’s only American visitors to Oz never to do so.

The question is, why are they so unhappy and unfit in this fairyland? It’s not because of the unpleasant kitten trial, which they participate in. (And they don’t seem too fond of the kitten.) Nor it is because they’re from California—Baum later introduced two other Californians, Trot and Cap’n Bill, who eagerly accepted a home in Oz. Nor is this a repeat of Dorothy’s desperate wish to return home. Jim, as he frequently relates, is only a tired old cab horse, worn to near—but not complete—uselessness in Chicago, and his return to California means returning to work. Zeb’s “home” is with an uncle who pays him a decent enough wage, but displays little affection. Nor is it because Oz is not quite the perfect fairyland that it would be in later books; both the Wizard of Oz and Bellina happily accept homes in Oz, whatever its flaws.

Maybe they’re just underwhelmed by Ozma. This, the second glimpse of Ozma as ruler, like the first, does not bode well. As Eureka the kitten points out, the “trial” Ozma presides over is little better than a farce. The kitten’s defense attorney is inept, and the supposedly virtuous princess of Oz is more than happy to condemn the kitten—the pet of her closest friend—to death on exceedingly tenuous evidence. Even as a kittenless kid, I found myself saying, lady, if you did this to my kitten, I’d so Magic Belt you.

But Ozma’s myriad flaws as a ruler can’t completely explain their discomfort either. Something else seems to be going on: a not-so-subtle suggestion of what Baum would make explicit later. The paradise of Oz is not meant for everyone, and not even meant for those who might, under work-ethic standards, seem most deserving.

To add to the cruelty, Jim finds himself inferior to the Sawhorse, a substitute horse brought to life by magic, and thus faster than a real horse and utterly tireless. This may echo some of the concerns Baum heard from workers terrified that they would be overtaken by superior machinery. (In the previous book Baum had made a point of arguing that living creatures are superior to machines.) In this case, these concerns are valid. But not all is lost for Jim—he has a job to return to in the United States, away from the superior substitute horse. Which may be the clue right there.

I don’t think it’s entirely a coincidence that the only two Americans who do not stay in and never return to Oz just happen to be working males with jobs to return to. The paradise of Oz is for the misfits, for the Americans that cannot earn an elite place in American society through work for one reason or another. They are girls (Dorothy, Betsy Bobbin and Trot); failed farmers (Uncle Henry and Aunt Em); unwanted vagabonds (the Wizard and the Shaggy Man); disabled (Cap’n Bill); and Button-Bright (who…doesn’t exactly fit this category, but already appears ready to embrace the vagabond life at a young age.)

Zeb and Jim, as workers, do not fit this mold. It’s an interesting, subversive argument against the American work ethic.

Then, too, this is the first Oz book where the characters are unable to rescue themselves without resorting to magical aid—Ozma needs to use the Magic Belt to save them from the final trap. And the first where the characters are unable to use ordinary things—eggs, water—to defeat magical beings; they must fight magic with magic. And even after they kill a sorcerer—in a scene that gave me nightmares as a child—they must flee the vegetable land in terror, rather than leaving in triumph, and survive in the next lands only through magical means. Perhaps it’s no wonder, then, that the old cabhorse and the teenage boy, capable only of ordinary things, find themselves so alienated in Oz.

Mari Ness would happily live in Oz, even it meant endlessly sitting on juries for kitten trials. She lives in central Florida, which if not Oz, still has its own kind of magic.